Exploring the ‘Platonic Space’ of Cognitive Archetypes

An Epistemic Journey into the Intuitive Process of Knowing

This essay is an updated version of a previous post, including a healthy dose of new quotes, metaphors, examples, and lines of reasoning.

***

This essay is intended as an epistemic journey into the process of ‘knowing’ and ‘explaining’, which is at the foundation of all human endeavors. Whether we are navigating our daily tasks and relationships, innovating with art and technology, or exploring the deepest existential questions, we do so by observing, discriminating, evaluating, and anticipating the lawfulness of our experiential states through our cognitive faculties, i.e., perception, memory, reason, and intuition. By communicating the results of this knowing process with others, human civilization emerges, is sustained, and advances. As adults in the modern intellectual age, we carry out this knowing process quite habitually. We pay little attention to how it unfolds and take it for granted as something we can ‘just do’. To what do we owe this remarkable knowing capacity, and how can we learn to observe its characteristic qualities and movements, potentially optimizing its functioning? As a convenient reference point for this inquiry, we will introduce the trailblazing scientific research of Dr. Michael Levin on embodied cognition.

In a recent article, Dr. Levin asked the question, “How best to explain the properties and capabilities of embodied minds?”. The rest of the article explored ways of addressing that question and concluded:

The only thing that can be said strongly at this point is that our ignorance about the capabilities of matter together with the patterns that ingress into specific architectures is vast [133, 134]. Technological and ethical progress now requires immense humility on the part of 1) scientists and engineers, to understand that arrangements of matter may not make life and mind as much as they midwife it, and 2) on the part of philosophers and spiritual leaders to resist thinking that they know what kind of embodiments ineffable minds may or may not ingress into.1

Dr. Levin rightly encouraged humility on the part of scientists and engineers who tend to reduce mind and life to arrangements of matter, even though there are no conceivable mechanisms through which the latter could ‘emerge’ into the former. That is why abiogenesis and the ‘hard problem of consciousness’ continue to be thorns in the side of the reductionists. He also encouraged humility on the part of philosophers and spiritualists who may dogmatically assert what arrangements of matter can embody the qualities of mind. When such thinkers postulate that mental qualities and capacities only belong to animals and humans, it blinds them to the cognitive-like behavior of biological systems. In both cases, the thinkers are reducing the complex dynamics of phenomenal experience into rigid frameworks and conclusions according to their preferred narrative.

Dr. Levin invites us, instead, to patiently explore phenomenal relations through observation and experimentation, remain attentive to their lawful dynamics, and let them speak their essence to us without prejudice. That is the phenomenological method of science that was originally pursued by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe in the late 18th century (contra Newton, Kant, et al.), for example. Goethe applied this method in the domains of optics, botany, and zoology and attained striking insights that many thinkers are just now coming to terms with. Yet, if we pursue this method, we also need to contemplate just how deeply our modern prejudices and intellectual pride may be rooted. What is the nature of the assumptions, preferences, and personal colorings we bring to our research, and how can they be made more transparent? How else are we overestimating our intellect’s ability to usefully answer such research questions via our theories and models?

Aristotle laid the foundational epistemic principle of scientific research several millennia ago, where the researcher should first purify the cognitive instrument by which they conduct inquiries into the natural world.

We must, with a view to the science which we are seeking, first recount the subjects that should be first discussed. … For those who wish to get clear of difficulties it is advantageous to state the difficulties well; for the subsequent free play of thought implies the solution of the previous difficulties, and it is not possible to untie a knot which one does not know. But the difficulty of our thinking points to a knot in the object; for in so far as our thought is in difficulties, it is in like case with those who are tied up; for in either case it is impossible to go forward. Therefore one should have surveyed all the difficulties beforehand, both for the reasons we have stated and because people who inquire without first stating the difficulties are like those who do not know where they have to go; besides, a person does not otherwise know even whether he has found what he is looking for or not; for the end is not clear to such a person, while to him who has first discussed the difficulties it is clear.2

In that spirit, let’s now take a step back to the original question – “how best to explain the properties and capabilities of embodied minds?”. Most people would feel that the meaning of such a question is already clear - particularly what it means to ‘best explain’ - and the primary task is to try and answer (not understand) the question. Is it possible, however, that moving directly to answering the question is putting the cart before the horse? Asked another way, are there any hidden presuppositions embedded in our concept of ‘explanation’ that may lead our thinking in a suboptimal direction for answering the question? If we don’t address the question before the question, so to speak, then our initial presuppositions will remain embedded in our subsequent reasoning, steering it in this or that direction, and we remain none the wiser. The question before the question prompts us to first explore what is directly given to experience while resisting any assumptions or inferences. It is given that, whenever we attempt to ‘explain’ some phenomenal experiences and their lawful relations, we utilize our thinking in a certain way.

We can better appreciate this if we imagine the last time we explained some aspect of our job, philosophical outlook, a life event, or something similar to another person. Since we were explicating familiar experiences and knowledge, it’s unlikely we needed to think too hard about each word before speaking. Instead, it is as if we immediately attuned our consciousness to certain intuitive ‘streamlines’ of meaning associated with those experiences and seamlessly focused the intuited meaning into verbal forms, as if through a prism. It is useful to introspect and ask, "What sort of meaningful context of experience am I drawing on to explicate my knowledge of X, Y, or Z?” We can't look and point at some “intuitive context” as a distinct perception in consciousness, like a color or sound, but that makes it no less real or important. Instead, we can try to feel this invisible intuitive background and follow as tightly as possible how our explaining thoughts manifest as if in the streamlines of the intuitive flow. There are many memory states, ideas, and capacities implicitly embedded in that flow, but we normally only pay attention to the content of the finished explanatory thoughts.

To avoid constructing yet another abstract ‘explanation’ for our intuitive thinking process, we need to approach this process in a somewhat different way than we approach the ‘objective world’ of phenomenal relations. We can no longer pretend to be a 3rd-person observer of a hypothetical ‘intuitive process’ who stands back from that imagined process and tries to model it with our mental pictures, like we do with physical objects. In that case, the real-time process that is doing the modeling remains merged into the background and is never accounted for by the mental pictures. Unlike what we are used to with physical objects, the intuitive process does not remain static as we try to investigate it. To put that in a metaphorical image, it's like someone who desperately hopes to capture their real-time neural activity by doing ever-faster MRI scans and reading the outputs which, however, can only reflect past neural states. Instead, the concepts we use to describe this intuitive process need to become less ‘explanatory’ in the usual theoretical sense and more symbolic of our inner flow. That is, the descriptive concepts can be understood as being more akin to climbing holds that help us get a firm grip on our dynamic, real-time intuitive process as it continually morphs and unfolds.

That is always how our concepts are functioning in philosophical and scientific inquiries, but we normally ignore that function and combine our concepts to form rigid explanations and extrapolate past patterns of activity into the future. In the metaphor, that would be like moving the climbing holds around into neat patterns that we passively contemplate, while forgetting that they were placed as such to help us scale the wall. The epistemic question of our time is whether we can leverage our conceptual pictures to scale the wall of our real-time intuitive process. To answer this epistemic question requires a participatory approach that has so far been undervalued, since the critical approach to epistemology inaugurated by Immanuel Kant came to dominate the thinking of philosophers and scientists. Certain thinkers like George Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel perceived that an inquiry into ‘what it is possible to know’ can only be answered by the thinking subject immersing itself in the real-time flow of cognitive activity, instead of passively analyzing ‘the structure of cognition’ with crystallized thoughts.

A main line of argument in the Critical Philosophy bids us pause before proceeding to inquire into God or into the true being of things, and tells us first of all to examine the faculty of cognition and see whether it is equal to such an effort. We ought, says Kant, to become acquainted with the instrument, before we undertake the work for which it is to be employed; for if the instrument be insufficient, all our trouble will be spent in vain. The plausibility of this suggestion has won for it general assent and admiration; the result of which has been to withdraw cognition from an interest in its objects and absorption in the study of them, and to direct it back upon itself; and so turn it to a question of form. Unless we wish to be deceived by words, it is easy to see what this amounts to. In the case of other instruments, we can try and criticise them in other ways than by setting about the special work for which they are destined. But the examination of knowledge can only be carried out by an act of knowledge. To examine this so-called instrument is the same thing as to know it. But to seek to know before we know is as absurd as the wise resolution of Scholasticus, not to venture into the water until he had learned to swim.3

With that said, we can begin swimming in the waters of our cognitive flow through what follows. Imagine you are playing a game of chess and lose. When later reflecting on the game play, you say to yourself, “I should have taken the pawn with the bishop on move 21!” We rarely introspect this process, but if we took the time to do so, we would notice that the words anchor our inner activity. This activity steers through a ‘memory panorama’ reflecting the prior game play, the rules of chess, our prior chess games, chess lessons, and so on, while also simulating potential pathways of chess states that would have unfolded if we had made a different decision. This whole meaningful panorama is compressed, so to speak, into our simple verbal statement. How often in life do we think things like, “if only I had done this instead of that…”? In that sense, our cognitive activity is continually exploring the intuited lawfulness of our experiential states and simulating potential pathways of experience that may unfold from various decisions, but normally that inner process is ‘drowned out’ by the verbal or pictorial anchors we utilize.

This inner principle applies to scientific inquiries as much as it does to a game of chess or daily life. To use a relevant example, Dr. Levin and his team have conducted experiments with planaria flatworms in which they ‘rewrite’ the worm’s bioelectric patterns such that the biological machinery manifests the potential of growing two heads instead of one. How did such an experiment originate? First, it was an idea in the consciousness of Dr. Levin and his team. They ‘extended’ their imagination into this space of meaningful potential and intuited certain possibilities for manipulating the bioelectric patterns and actualizing new forms in the worm’s morphological space. We are not suggesting that their imagination is the source of such lawful possibilities, but it is undeniably the case that the latter could only come to physical expression if the researchers involved first extended their thinking into intuitive space and probed its potential. That is also made clear by Dr. Levin in another recent paper (emphasis added):

Planarian flatworms, which normally regenerate the correct heads with nearly 100% reliability, can be induced to make heads of other species – without any genetic change but by disrupting the bioelectric circuits that store the target morphology.4

If left to themselves, the flatworms will regenerate the ‘correct’ heads without fail, like a seasonal plant will always produce the same blossom or fruit when it regrows. It is only when these biosystems leverage the creativity of human intuitive space that they are induced into exploring radically novel pathways of development within morphospace. If we are trying to be as complete as possible in our account, we should note that, in some mysterious way, the human intuitive space acts as the stage on which the drama of creative morphological exploration unfolds. Humanity has instinctively pursued this participatory role for many millennia of breeding plants and animals, for example. We are not surrounded by many animals with multiple heads, or limbs growing from odd places, because such potential outcomes are only explored and manifested through the activity of human imagination (for better or for worse) and that imagination has so far been relatively constrained (which is quickly changing, as we can see from Dr. Levin’s research).

Thus, before we try to ‘explain’ the experimental results surrounding embodied minds, it is incumbent that we better understand the cognitive process by which those results were made possible, especially when the potential consequences of our experiments have grown so far-reaching. That doesn’t imply we are floating off into our imagination and forsaking the experimental process, but rather we are trying to refine and better orchestrate the latter by exploring the intuitive process that is always prior to the experiments and explications. There are broadly two distinct ways in which we can utilize our intuitive process to ‘explain’ various phenomenal relations. These are not fundamentally different ways of thinking, but rather they arise from the manner in which we relate to and understand the mental pictures we weave together in the unitary act of thinking, i.e., the memory images, words, mathematical symbols, etc. that we condense and manipulate with our cognitive activity.

As described above, whenever we contemplate phenomenal experience, we instinctively steer our cognitive activity through the panoramic intuited meaning of that experience and focus this meaning, as if through a prism, into our mental images, verbal thoughts (the ‘inner voice’), and physical gestures (speech, sign language, etc.), which stabilize and anchor the intuited meaning. These images, verbal thoughts, and gestures function like iron filings that help us conceive of the invisible ‘magnetic force lines’ along which they cohere into meaningful patterns, pointing our attention toward invisible streamlines of intuitive potential while also giving our inner activity firm support to explore that potential. We sometimes also conduct these imaginative symbols through our physical will, e.g., when pursuing physical tasks like conducting an experiment in the lab. That is true whether we are steering our thinking through the transformation of (quantized) sensory states in natural scientific inquiries or the transformation of our mental states when engaging in pure mathematics, playing a game of chess, or planning our daily schedule.

To attain a more refined feeling for this intuitive process, let's imagine that we concentrate on the title of a song that we are familiar with. We have a mental image at the focus of our conscious experience which anchors our overall intuition for the sphere of potential experiences that can manifest if we were to start singing the song. That is, we have some intuitive sense for the time span of the song and the rhythmic transformations our inner voice would have to go through. We can approach a similar intuition if we simply try to feel what a minute or an hour is, not by abstractly philosophizing about it or imagining a clock, but by trying to stretch our inner life in all directions as if to feel how our present ‘ticking’ of thinking states is embedded in a greater rhythmic flow. Now we live in a holistic intuitive state that feels dim and nebulous, like a ‘superposition’ of all the potential meaningful experiences that can unfold from the ‘playback’ of this intuition.

Then we can begin singing the song, experiencing the playback of our holistic intuition. Now our singing mental voice moves through the 'intuitive curvature' that was previously anchored in the song title. There are many audial perceptual elements in this playback - our words are not only monotonically pronounced, but their pitch is bent up and down according to the melody. The melody can be grasped as repeating patterns grouped in measures, phrases, verses, and so on. Notice how all these diverse perceptual elements are explained through our intentional activity that unpacks the holistic intuition of the song title. We know them by feeling how we live in something meaningfully intended, which we can’t encompass as yet another perceptual element, but which clearly gives us intuition for the way the multiplicity of phenomena unfold, i.e., from whence they came, how they relate to one another, and to whence they are going.

As another helpful example, we can imagine that we decide to slowly progress through the numerical concepts between “1” to “10” in our mind. As we progress from pronouncing "1" to "2" to "3", etc., we have a very clear intuitive sense of how our momentary verbalizations are structured through time. The auditory vibrations of our inner voice, as we pronounce the words of the numbers, do not meet us like a mysterious foreign object, for example, the erratic movements of a fly buzzing around, but as an orderly progression of inner counting states guided by our meaningful intent to count. If we are currently at "5", even though we haven’t yet reached ten, we have a good intuitive sense of where the process is going and what inner state will soon condense at our mental horizon, even though we haven’t yet pronounced the next numbers in our mind. This intuitive sense also gives us orientation for how we have reached our present “5” state through the previously pronounced numbers. All the imaginative states experienced while counting feel like they precipitate and flow along the ‘curvature’ of our intuitive intent.

We always experience this intuitive thinking process, but normally we have very little consciousness of that experience and, instead, we feel involved in another process. To better feel the contrast between the two, we can imagine that, just when we pronounce "5", we somehow forget that we are intentionally counting. Then we hear in our mind "5", but it sounds like a thought that randomly pops in our mind. We have no intuitive sense of why it appeared or that something else should appear afterward. In this case, we make a mental picture of the sound "5" and then try to complement it with other mental pictures that should 'explain' it, like chemical reactions, neurons, supernatural beings who projected the sound in our mind, and so forth. We feel satisfied with our explanation when these mental pictures are snapped together like puzzle pieces and seem to make intuitive sense, i.e. they feel internally consonant with each other and with other phenomenal facts of experience in a way that we call ‘logical’. Notice, however, how this explanation made of snapping mental pictures together remains abstract, and we don’t know whether our mental puzzle faithfully reflects reality, even though the pieces may fit together very convincingly.

Now we can contrast this ‘mental correspondence’ process with the experience of suddenly remembering our counting activity. This provides us with a completely different kind of ‘explanation’ for “5”. We no longer need to assemble mental puzzles to find an explanation for it, but instead, our remembered intent to count fills the vacuum and makes intuitive sense of why the "5" appeared in our consciousness. The fact that these different explanatory approaches emerge from forgetting or remembering what we are always doing with our cognitive activity illustrates how the difference is only a matter of conscious perspective on our mental pictures and their lawful relations. When we remember our intent to count, our perspective on the “5” inverts and we feel that our intent becomes the explanation that we were otherwise seeking through abstract arrangements of mental puzzle pieces. This inversion can be metaphorically depicted as the shift in perspective that allows for hidden images to emerge from the flattened pixel patterns of a Magic Eye stereogram.

Those of us familiar with these stereograms probably remember the frustrating experience of trying to stare intensely at the pixels and analyze them in some way until we see the hidden image. We may have tried to isolate certain parts of the pixels and then combine them in ways that could potentially reveal a new image. After learning that this effort leads nowhere, perhaps we loosely gazed at the patterns until the hint of some new image began to take shape. Yet, as soon as that happens, our mind typically latches onto the meaning of that hinted image, like Eve unfaithfully grasping at the apple, and then everything quickly flattens out again. The hidden depth image is always there, like a ‘wavefunction’ of holistic meaning, but normally our cognitive perspective is conditioned by habits that collapse its potential emergence. Then we end up manipulating flattened pixel patterns analogous to the standard explanatory approach in scientific inquiries. In this latter case, we don’t even suspect that a new kind of inner effort and perspective would naturally reveal the depth image embedded within the pixel patterns in a sustained way.

If we begin to pay careful attention to the flow of experience, we will notice that most phenomena in our sensory and psychic environment meet us exactly like flattened pixels with little relation to our cognitive agency, i.e., like the "5" sound after we have forgotten our intent to count. If we are honest with ourselves, we don't feel like these phenomena, including our impulses, moods, and emotions, are guided along the 'curvature' of our meaningful intents like the counting states. Instead, they are more like the erratic fly buzzing around; we dimly sense there is meaningful activity going on, but the patterns of that activity feel like relatively isolated phenomena without a clear sense of from whence they came and to whence they are going. A sour mood or negative thoughts may periodically wash over us even when we intend to be uplifted and positive. The majority of thoughts also pop into our minds based on various mysterious triggers, and we passively surrender to this stream of intellectual commentary throughout the day. Thus, our default state is one in which we feel compelled to construct flattened pixel puzzles to gain at least some sense of lucid orientation within the dynamic flow, but this comes at the expense of the hidden depth.

A helpful image for this ordinary life situation is a chessboard after about 10-15 moves, if we imagine we popped into existence at that board state without any previous memory of the game flow.

We awaken in our cognitive life immersed in complicated transformations of sensory perceptions, thoughts, feelings, and impulses (from the personal to the collective scale), which all transform in their unique lawful ways, without any lucid awareness of how we got into this particular state. The pathways of experience that resulted in the state were traversed entirely instinctively in childhood and early adolescence, as if we were dreaming through it all. Through our instinctive natural development, we have developed a dim orientation to the complex lawfulness of the transforming phenomena (analogous to the rules of chess), but if someone were to ask us why the knight is placed on this or that particular square, we could only come up with some post-hoc mental puzzle to explain its position. The modern explanatory intellect is much like a person who only studies the mechanical movements of the pawns (the quantized states of visual sensations and corresponding memory pictures) and tries to extrapolate the lawfulness of the dynamically moving rooks, knights, bishops, and queens exclusively in terms of mechanical pawn-gestures.

Once again, we can contrast that with the intuitive orientation we would experience if we were playing the game and moving one set of pieces. Now we have a clear sense of the ideas we were working with as white or black, which eventually embodied itself in this particular board position. Our ideas were not static objects but dynamically unfolded across time according to the constraints of the chess rules and our opponent’s ideas. The latter continually impressed into our state and nudged our thoughts and decisions in this or that direction. The more we could resonate with those ideal influences, the more coherent our intuitive orientation would be to the present board state. That perceptual state then acts as a rich anchor for our intuition of the dynamic game flow. This complex flow involves not only our cognitive intents but those of at least one other agency. The perceptual board state stabilizes our temporal intuition and provides a basis for us to intuit new possibilities of movement toward the realization of our goal.

When we move from such examples involving strictly human agency to the domain of biophysical configurations, it is typical to revert our perspective from the intuitive thinking process into the mental correspondence approach. Thus, we observe lawful patterns and cognitive-like properties in the biological and physical spaces and wonder, ‘how best to explain them’, i.e. how best to click together mental puzzle pieces until they feel convincing enough to serve as a replica for the ‘true reality’. With this approach, even though we may caution for humility, we are necessarily elevating our abstract mental puzzles into the domain of ‘true knowledge’ about the phenomenal experiences we are contemplating. Another helpful image for this mental correspondence process is if we imagine taking finger nails (thoughts) that have been clipped from our hand (intuitive thinking process) and, instead of retracing these dead nails to the living limb from which they grew and precipitated, we assemble the clipped nails into the shape of a “hand”. Then we habitually confuse our hand model for the living hand from which our nails were clipped.

The intuitive thinking process, on the other hand, does not forsake precise observation and logical thinking but admits that these, without a ‘Magic Eye’ shift in cognitive perspective, are insufficient to reach the true hand, i.e. the ‘Platonic space’ of ideal activity which is embodied in the psychic and biophysical spaces that we are always recursively utilizing to contemplate those spaces. To accomplish that shift, as we saw with the counting and chess examples, it would make the most sense to begin the 'explanation' of the properties and capabilities of embodied minds in our embodied mind, i.e., in the intimate domain of our real-time cognitive process where we feel to have lucid clarity of the metamorphoses of mental states. We only know how to conceive the meaning of ‘Platonic minds ingressing into biophysical patterns’ because we experience how our intuitive process ingresses superimposed meaning into imagistic and linguistic patterns. Thus, we are exploring the process by which we make sense of observed morphological and behavioral patterns, but normally leave cemented and unquestioned. We routinely take our thinking out for ‘test drives’ but rarely examine what kind of combustion processes are going on ‘under the hood’.

When we take this living process for granted, it doesn’t occur to us that there is hidden depth to it that can be explored, which would unsurprisingly lead to the explanations we are always seeking through that process (but not necessarily in the computational format that we are expecting to find them). We realize that it couldn’t be any other way. If our explanatory mental pictures about the embodied patterns have precipitated from the living thinking process (like fingernails from a living hand), then it is most natural to seek the deeper reality of those patterns within that same process as it unfolds. The central difficulty for the intellectual thinker in our time is that this real-time process is left unexamined, not because it is technically difficult to examine, but because it isn’t even suspected that such an exploration is possible or worth pursuing. We should try to better appreciate how this obstinate attitude toward the intuitive thinking process takes shape.

We can imagine a person sitting on a couch in a dark room and holding a tablet. This person cannot see his body or fingers, but can only see the screen. He instinctively touches the screen and navigates through apps, websites, etc. The person says: "These movements on the screen just appear and I don’t know what is responsible for them." He only observes the movements (thoughts) on the screen and half-consciously slides his finger around. When asked about these moving shapes on the screen, he types in the chat with his fingers (which he doesn't see): "The words just appear and communicate meaning, but there's no one typing them". That is, the in vivo thinking perspective, which gives this ‘explanation’ of the thoughts appearing on the imaginative screen, remains completely in the blind spot of consciousness. It creates an explanatory mental puzzle for the already past movements and shapes, but this puzzle never captures the present explaining process.

As a related metaphor, imagine we are taking a walk outside on a foggy day. As we walk, some faint golden sparkles begin to materialize out of the dense mist. They gradually grow more intensely luminous and, as that happens, we sense they are communicating meaning to us. We begin to sense they are telling us interesting secrets about the structure and dynamics of reality. They reveal insights about the way rivers flow, plants grow, animals behave, and such. In this scenario, would we not begin to wonder about the origin of these sparkles, to question from whence they came, how they manifested out of the fog, how they relate to one another, and so on? Perhaps not, if we were poorly written characters in a thriller movie; the type who never think through the implications of what is happening around them. In real life, however, most people would not simply take the appearance of these golden sparkles for granted and focus exclusively on the content that was communicated. They would feel a burning need to inquire into what the existence and manifestation of these sparkles imply about the structure of reality, which they previously felt was practically ‘all figured out’.

This imagination can help us better appreciate the oddity of how we relate to the mental pictures by which we build our mental puzzles, which are exactly like such golden sparkles of meaning. We focus entirely on the meaningful content of those pictures but leave the process of their wondrous manifestation unquestioned. The inner process through which these pictures condense out of the dense fog of intuitive consciousness is left unexplored. In that sense, the portal to the Platonic space of patterned intelligence has been hiding in ‘plain sight’, right within our most intimate experience of shaping mental pictures to re-present the meaning we are intuitively steering through and orient ourselves in the dynamic flow of existence. Why do we so habitually avoid entering through this portal, then, if it is in such close proximity to our conscious perspective? Perhaps we have grown so accustomed to feeling in control of manifesting our sparkly thoughts that we are fearful and hesitant to experience any other formative influences at work in that process.

We can acclimate to this possibility by imagining either a green or a red cube. We begin with an imaginative ‘wavefunction’ of both possibilities, superimposed. Now we can try and observe what we do in our inner process to 'collapse' our imaginative flow toward one of the two cubes. It is very elusive. We may feel as if we balance a stick on our finger until, at some point, we decide to drop it to the left or right. Often, we lose our balance but decide, after the fact, to act as if it was our free choice. Maybe there was wind, our hand was shaky, we have a secret bias for one of the directions, etc. In physical life, we can’t ignore the existence of the wind, but in our imaginative life, we habitually ignore the ‘winds’ that steer the ripples of our thoughts. The other possibility is to make a reasoned choice and reach 'green' or 'red' as the end token in a chain of thoughts. But that only displaces the problem because now each thought of the chain poses the same question – why did we travel down this particular line of assembling mental puzzle pieces and not another one? When we introspect through such simple exercises, we can gradually grow more sensitive to the mysterious constraints on our cognitive flow.

Recovering sensitivity to our real-time intuitive process, as we ‘explain’ the world around us, is not only a technical cognitive skill, but also implicates our moral life of feeling and volition. As infants, before we become too habituated to our bodily life, i.e., its constraints and possibilities, we naturally approach that life with an instinctive enthusiasm and wonder. The whole bodily environment becomes fertile soil for imaginative play and exploration. It is similar with our intellectual life in early childhood. Yet, after engaging in the same bodily and intellectual movements over and over again, becoming highly conditioned to the meaningful feedback on those gestures, our enthusiasm and interest wanes. As Samuel Taylor Coleridge put it, “in consequence of the film of familiarity and selfish solicitude, we have eyes yet see not, ears that hear not, and hearts that neither feel nor understand.”5 Thus, the first step is to restore a childlike sense of reverence, wonder, and enthusiasm for the imaginative sparkles of our cognitive life and the mysterious constraints that shape them. Hopefully, we have already attained inklings of that restored sensitivity through the various illustrations and exercises above. We may have already experienced new degrees of imaginative freedom and a slightly different vantage point on our ordinary thinking flow.

In a certain sense, our inner activity needs to ‘shrink’ itself back into an embryonic state and once again experience the surrounding world as a peripheral environment of potential that can be gradually explored in an intuitive and imaginative way and, eventually, shaped creatively. Our bodily structure and processes, temperament, character traits, preferences, etc., normally feel like a tightly fitting mask that we are merged with, so we need to create new leeway in this mask. It is a kind of second birth within the intuitively conscious life. Dr. Levin has had much initial success in his research pursuits in large part by looking at familiar biophysical phenomena as if for the first time, but now this inner stance can be extended to the activity of ‘looking’ itself. As discussed above, we are putting the cart before the horse if we don’t first enthusiastically inquire into the cognitive process which makes our biophysical experiments possible, as if we have never looked at it before (indeed, many people never have). Before we start manipulating the patterns of morphospace, we can consider working on the disharmonious patterns of our own thinking space.

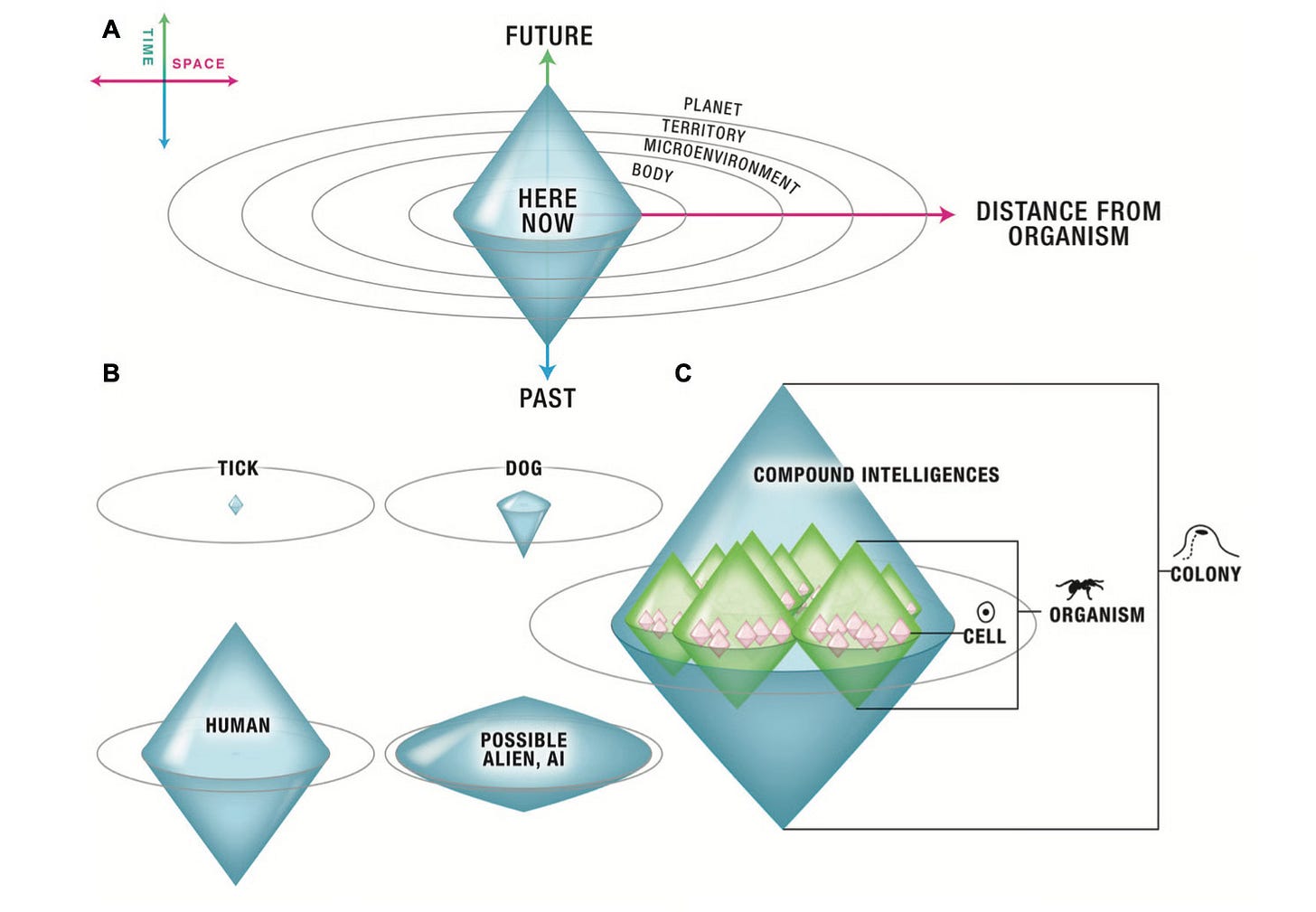

Dr. Levin often refers to the ‘cognitive light cones’ of various embodied agents. This term symbolizes the fact that agents are capable of creatively steering their present state toward goals with shorter or longer timespans. In the case of human agents, unlike plants and animals, this can include goals that even outlast the agent’s lifetime. The human cognitive light cone also encompasses the lower-order light cones of animals, plants, etc. If we take this symbol a bit more literally, we can imagine that the experiential reality of these other cognitive agents is to be found within the depths of the human-scale cone. By tracing the movements of our human-scale mental pictures to their living source, we are also directly encountering the Platonic space of cognitive agents that we otherwise think about abstractly through the assembly of our mental puzzles. In other words, the perceptions at the tip of our human-scale cone implicitly embed the meaning of the cones along the entire Platonic gradient, from the shortest to the longest temporal wavelengths (including potentially supra-human agencies that inspire ideals outlasting a lifetime).

This principle is conspicuous when we consider the products of human culture. For example, if we are contemplating how each town has a courthouse, we instinctively sense that the best way to understand this patterned appearance is to explore the human ideas invested in city planning, architectural design, the ideals of fairness and justice, and so on. These cultural products were all first lived out through impulses and ideas before they were physically manifested and shaped our modern environment. Preferably, we start with ideas from recent times and only later expand into the whole history of civilization. It is implicit that the more our thinking thoroughly probes such domains of intuitive meaning, as if feeling out their ‘inner geometry’, the more we will be able to lucidly explain the patterned appearance of courthouses. Is there any reason this same principle should not apply for the patterned appearances of natural objects and processes?

The LIFO (last in, first out) principle in computer programming can be metaphorically instructive here. Since the human cognitive process, which explores existence through its stream of reflective mental pictures, was the last to arrive in World evolution, it should be the 'first out', i.e. the first to be turned inside-out and intuitively understood. We can't undress our socks (the physical patterns of the biological space) before we first untie our shoes (the psychic patterns of our human cognitive space). To use another metaphor, we can imagine our real-time cognitive process, by which we try to explain the ideal patterns embodied in the biophysical space, is where the Platonic space is most 'in-phase' with its embodied perceptual forms, i.e. our intimate stream of mental images, verbal thoughts, and symbols. The latter feel like they closely mirror our cognitive intents and activity. The intuitive experience of their unfoldment along the ‘curvature’ of that intentional activity also explains their embodied cognitive properties.

The biological-physical forms, on the other hand, are initially quite out-of-phase with their corresponding Platonic archetypes. When we intend to move our arm, for example, the perceptions may or may not mirror our cognitive intent depending on the independent state of our body, i.e. whether it is in good health, our arm is sore, our joints are stiff, we are paralyzed, etc. Even when the arm movement feels to faithfully reflect our intent, we have little clarity on the inner biophysical process of the nerves, muscles, cells, etc. that make this movement possible. Here there are mysterious archetypes at work that feel unrelated to our lucid cognitive agency and thus we feel they need to be ‘explained’ by mental puzzles. We sleep through that entire biophysical process, while we feel much more awake in the weaving of thought-images when doing philosophy, math, or simply imaginative exercises like the counting exercise above. This in-phase level of awakeness allows the intuitive process to fill the vacuum and become our explanation of the experienced patterns.

To his credit, Dr. Levin intuits this overlap between the Platonic space and our intuitive space when he explores the dynamic patterns of logical thinking constructs (e.g. the Liar’s Paradox), which he calls “obvious denizens of the Platonic space”6. The oscillating binary movements of the intellect can be made the object of intuitive observation, and graphs can be used to create a metaphorical map that helps anchor our intuition of those movements. Yet logical thinking of this sort is only a fraction of our lawful and archetypally structured intuitive space and we can’t forget about storytelling, art, music, creative innovation, and so on. Isn’t it possible that in the movements of a musical symphony, for example, we have a more faithful anchor of our Platonic intuition than in the movements of a computational algorithm? Perhaps the aesthetic and moral impulses weaving in our consciousness when contemplating artistic images evoke the meaning most proximate to the native essence of the Platonic space. For example, we can try to sense the archetypal feeling movements that entrain our mental states when listening to the following well-known opening measures:

If we concentrate and focus on our inner experience (resisting a strictly sensual enjoyment), we can dimly feel that our consciousness is ‘bouncing along’ with the archetypal gestures of these layered movements and articulations. Our mental images feel like overtones modulated over the subharmonics of deeper impulses. The experience of these inner movements, however, cannot be clearly defined and computed. This contextual inner structure cannot be formatted into convenient equations and graphs, yet that makes it no less real or important for exploring the Platonic space. If we want a more complete image of this space and its ingressing patterns, then we can’t only focus on the computable meaning of our isolated sensory transformations but should also account for the deeper life of holistic and narrative meaning that speaks to qualities of enthusiasm, heroism, courage, and so on (and the negative counterparts of such qualities). We can also have a reasoned faith that reality is essentially continuous, i.e., that there is no need to believe in an insurmountable experiential gap between the intuitive clarity of our imaginative space, which explains the embodiment of human cultural patterns, and that of the biophysical spaces.

Such discontinuity can only remain an abstract belief that we choose to blindly accept. It could never be verified because the cognitive act of verification implies intuitive continuity within that domain of experience. Instead, we can humbly and patiently retrace our imaginative states into the deeper psychic and biophysical rhythms that contextualize their unfoldment. When we chose to read this essay and participate in the counting exercise, for example, we were led into the vicinity of that by certain ideas, interests, preferences, sympathies and antipathies, linguistic capacities, and so on. At the same time, our capacity to count rests on the support of our brain and physical organs working in concert. In that sense, we can approach these deeper scales of experience insofar as we can intuit how their rhythms steer, shape, and constrain the real-time flow of our imaginative contents. These intuitions can then be artistically painted with precise descriptive concepts which anyone can use to anchor their own intuitive process and test against the facts of experience, as we have already started to do here.

Once again, to Dr. Levin’s credit, he has indicated we need a transition from 3rd-person observation and mathematical modeling to 1st-person experiential investigation. He suggests that we can only get so far speculating about the properties of ‘embodied minds’, ‘collective intelligence’, and so on, as an external observer, and rather we need to begin experiencing what it is like to be these non-human minds and this collective intelligence. Can we experience the transformation of experiential states from the perspective of such collective intelligence just as we experience the transformation of our imaginative states when doing the counting exercise? This question has become critical in our time and resides at the threshold of a major scientific paradigm shift. It is perhaps no overstatement to say that the future of humanity depends on how we approach and answer this question, and unfortunately, those who are seriously pursuing this intimate line of investigation are few and far between.

The issue is that Dr. Levin can only imagine the human agent tapping into the 1st-person perspective of collective intelligence through technological interfaces (which his team is working to develop in the lab). This indirect approach is imagined to be necessary because what we have discussed above is not yet suspected. It is not suspected that our 1st-person human thinking perspective, which imagines itself as a “3rd-person observer”, is already living within the collective intelligence from which we draw our intuitions and insights about such intelligence. In other words, the transition from 3rd- to 1st-person science comes from becoming more keenly conscious of what we are already doing with our intuitive activity when conducting the former. It is precisely the sensory interface and its technological extensions that obscure the real-time movements of that intuitive activity from ordinary consciousness. They function to scatter that activity into fragmented perceptual elements and thus drown out our experience of it, like the bright daytime sky drowns out the subtle hues of the starry firmament.

What Dr. Levin proposes to conduct as “1st-person science” is little different than what modern ‘psychonauts’ accomplish through ingesting physical substances or manipulating bodily processes in some other way, such as through holotropic breathwork. In this case, intuitive activity is loosened from its rigid neurosensory constraints and can reflect its experiential flow in more ‘exotic’ bodily processes (for example, those of the digestive system). This amped up bodily reflection can even spark visions and verbal communications which feel like they are issued from the Platonic foundations of reality, when in fact they symbolize personal memories, wishes, desires, ambitions, and so on. It is the same principle at work in our ordinary dream life where our bodily processes can transform into fantastic scenes that feel all too real, for example, a digestive process becomes a venomous pit of snakes. When we conduct research in this way, it is as if we have identified with various dream characters, who are all manifestations of our personal perspective, confusing them with the 1st-person perspective of ‘collective intelligence’.

In contrast, the path we have started taking in this essay already brings us into the vicinity of an alternative form of 1st-person science. We have attempted to ‘explain’ the nature of embodied cognition, not as passive observers of cognitive phenomena ‘out there’, but via metaphors and examples which immerse our consciousness in the dynamic flow of our real-time cognitive process. Altered states of consciousness brought about through physical substances or processes (like electromagnetic stimulation, bioelectrical manipulation, etc.) can only last as long as those substances continue to metabolize in our bloodstream or as long as we remain subjected to the relevant technological manipulations. The concentrated experience of the intuitive thinking process, on the other hand, is independent of all such physically determining factors. It even remains independent of psychically determining factors such as our prior beliefs, assumptions, interests, language, character traits, and so forth. Thus, it leaves our consciousness free as it explores the Platonic space and intuits the latter’s lawful dynamics.

The above image was taken on a sundial at approximately 11:30 AM. By observing the patterns of how such shadows cast, we can intuit the organic and lawful rhythm of the Earth in its relation to the Sun. This rhythm contextualizes our daily experiential states from waking to sleeping. The intuition of this rhythm can then be anchored with concrete mental pictures which reveal a twelvefold pattern, which can be further conducted through the bodily will and embodied in the technological extensions of that will. Thus, inventions like the sundial can arise. We are then using imaginative and physical space as an artistic map for our intuitive thinking process, which helps us refine and better orchestrate that process. It is the same principle at work in all of our scientific inquiries as well, which results in various theories, models, and explanatory frameworks that lead to new technologies. They are all originally rooted in our intuition of the rhythmic transformations of our experiential states, which are stimulated by the shadows (perceptual patterns) cast from the non-physical light of the Platonic archetypes.

But what are the shadows most relevant for human progress today? Those are the psychic patterns of thoughts, beliefs, desires, preferences, sympathies, antipathies, character traits, etc. that comprise our entire sense of personality or ‘self’. Hardly anyone can doubt that the most pressing issues facing humanity - war, environmental imbalances, social conflict, psychic (and even physical) epidemics, political corruption, and so on - are the result of disorderly human passions and insatiable desires for convenience, pleasure, power, status, and so forth. By orienting our perspective properly within the illuminating rays of the Platonic Sunlight, i.e. our real-time intuitive process, the shadows (thoughts and feelings) cast in our psychic life begin to feel like testimonies to the contextual intuitive rhythms that they anchor. Thus, we can attain intimate self-knowledge that also translates into the capacity to creatively ‘torque’ the disorderly psychic rhythms and bring them into alignment with the aesthetic and moral impulses of the Platonic space.

Imagine we are doing the counting exercise again, except this time when the audible state “5” condenses at our mental horizon, we resist allowing the next “6” state to condense. In other words, we are still intending to count to 10, but we don’t allow this intent to condense completely to a visual or auditory state. It is like we are damping and slowing down our inner activity to the stage that pronouncing a mental word feels ‘heavy’ (as if we are extremely tired and can hardly speak). It still requires full concentration, yet we intentionally damp down the intensity to the degree that the imaginative 'pixels' of the numerical state only 'buzz' in our consciousness but do not take the visual or auditory 'shape' that we intend. It is important to remain vigilant in this exercise and make sure we are not secretly whispering the words from the background. For someone who has never tried this before, it will feel practically impossible for at least a few iterations. The unchecked condensation of intuited meaning into pictures and words is something we normally allow to happen without any resistance.

The point of such an exercise is not to ‘succeed’ but to become more sensitive to what it means to reach a deeper scale of cognitive agency within the Platonic space. Put another way, the measure of success is precisely the extent to which we become more intuitively conscious of the ordinary constraints on our imaginative space, i.e., how these constraints are always subtly shaping, steering, nudging, etc. the flow of mental pictures by which we both construct our mathematical models of reality and navigate our daily existence. That consciousness eventually translates into greater degrees of freedom to torque the ‘rotations’ of the most proximate psychic constraints. Normally, we bounce rather chaotically between enthusiasm and apathy, indulgence and temperance, mental lucidity and fogginess, and similar polarities, like a two- or three-arm pendulum. With a deeper scale of effort, however, we can bring these rotations into a more harmonious balance, such that we are not always passively waiting to slide into apathy before we bounce back into enthusiasm for life experience.

Intuiting and torquing the psychic constraints also helps us more clearly discern what assumptions and preferred narratives we may be bringing to our scientific research (among other things). We can become much more conscious of what we are doing when choosing certain research paths and technological applications over others, i.e., how these intellectual scale decisions fit into a broader tapestry of Platonic intents. If we are open to the possibility that the Platonic space is comprised of non-physical minds, then it behooves us to inquire into how such minds pivot along the ‘geodesics’ at their corresponding scales and how such intentional movements project into our intellectual scale as the overlapping lawful transformations of the imaginative, biological, and physical spectrums. Then we may be in a better position to evaluate how the goals pursued within our human cognitive light cone harmonize or clash with the other human and non-human light cones along the full spectrum.

In that sense, there are many ethical implications that flow from whether we become more conscious of the intuitive explanatory process we are always engaged in but habitually fail to take notice of. There are serious consequences if we continue to imagine that the Platonic space can only be investigated through the interface of biological or technological embodiments, i.e., by building up mental puzzles and testing them against physical experiments or using technological means to alter our state of consciousness. If we acknowledge the reality of collective intelligence but refuse to explore how such intelligence is at work, first and foremost, in our intimate cognitive process, then our cognitive agency remains as a self-enclosed sphere that can only abstractly speculate about ‘other minds’ which feel orthogonal to our embodied mind. On the other hand, if we start our explanation with the intuitive exploration of the interfering intelligence right within our cognitive space, then we finally begin to close the experiential gap between science and spirituality, between manipulating existing forms and creating new forms, between knowing about reality and becoming a new reality through our knowing process.

Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, Encyclopaedia of the Philosophical Sciences, Part One (1830)

Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Biographia Literaria, Chapter XIV (1817)

Michael Levin, Id.